I’ve been trying to figure out how to start this piece for the last two days, and realized that I needed to make three things apparent right off the bat:

- I respect Gene Roddenberry’s achievements as Star Trek‘s creator and executive producer (for the first two seasons, at least.)

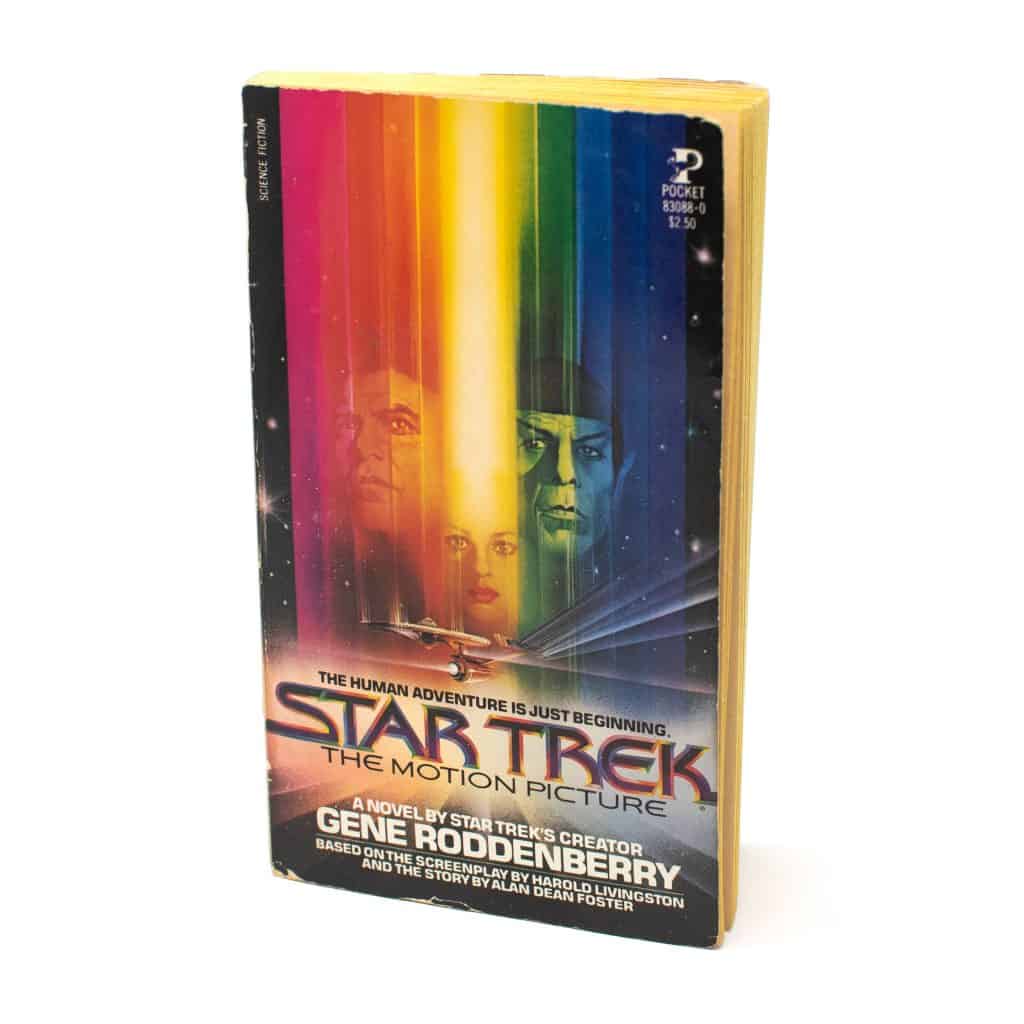

- His novelization of the first Star Trek film is not good. Its shortcomings highlight just how much people like D.C. Fontana and Gene Coon contributed to the series’ world and tone.

- The movie itself is problematic (yes, I love it, but c’mon) and should bear some of the blame.

Okay, there. Now, let’s dive in. I’m going to assume that you have a working knowledge of the film, and if you don’t, it’s available on Amazon Prime as of this writing.

Did Gene Roddenberry really write the novelization?

Yes, he did. Unlike George Lucas’s Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker or Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind — both of which were ghost-written by prolific science fiction author Alan Dean Foster — The Great Bird of the Galaxy himself sat down with a copy of the script (based on Alan Dean Foster’s story) and hacked this thing out.

That means that this book is a direct connection to Roddenberry’s vision for Star Trek, and boy, is it weird.

Wait, how weird?

James T. Kirk himself wrote the primary introduction to the book (there are two, which I’ll get into later), and on the very first page, he reveals that his first name came is a tribute to his mother’s “love instructor.”1There’s also a bit about how he got the middle name “Tiberius,” but nothing can compare to finding out that there are makeout coaches in the future.

That kind of weird, okay? But let’s stick to the very basics first, okay?

There are structural problems with the original film. It first two acts take forever and the finale is truncated and lacking any real emotional impact. A more experienced prose author could have ameliorated this a bit, perhaps by working through a straight first draft and then going back to nip, tuck, and expand to make the pacing more propulsive.

Gene Roddenberry was not an experienced prose author and it’s obvious that this book didn’t have a second draft. In fact, it feels like any editing on the book was restricted to checking the spelling. There are probably two factors at work here:

- I can’t imagine anybody wanted to be the person to tell the man who created Star Trek that he was doing a bad job at writing Star Trek.

- There was a hard deadline that had to be met.

Okay, so let’s start with the good.

Well, the five-minute Enterprise flyby only takes a page and a half instead of a whole chapter, so there’s that.

Okay, yes, there are things I liked about this book.

In the movie, Kirk’s arc feels kind of hastily sketched, but Roddenberry does a good job detailing what he goes through. He goes from being the dickhead who takes his ship back to the guy who tells the navigator to go “thataway” in a way that feels organic. The reader discovers that he’s basically a living symbol that’s being held hostage by Admiral Nogura because of his symbolic value (I’ll get into how in a bit because hooo boy) and we get to see him come back to life through his interactions with the rest of the cast.

Spock also gets a bit more time to shine early on, which helps his arc as well. We’re inside his head when he’s about to take the final kolinahr test and learn that he’s bidding farewell to Jim Kirk, his t’hy’la, when V’ger touches his mind.

(T’hy’la is a term that the slashier end of fandom latched onto quickly, thanks to a footnote by Roddenberry2You can read that footnote here.. I disagree with their interpretation, as I feel like healthy depictions of deep homosocial relationships are important in fiction. It should be noted, however, that I also feel like they can think whatever they want because slash helped keep Star Trek alive and I’m not the boss of them.)

Speaking of relationships, Decker and Ilia’s past gets a little more play, which makes them more than the rough draft of The Next Generation‘s Riker and Troi that we get in the actual film. They also get taken to some really unfortunately places, but, again, we’ll get into that.

V’ger (spelled phonetically as “Vejur” through the text, a decision that I simultaneously respect and reject in this post) gets an entire chapter told from their point of view. The reader gets insight into their journey and subsequent confusion at their creator’s silence. This short text helps sell the reveal at the end by making them seem truly alien.

As far as plot elements go, Roddenberry’s book does do one thing right: it adds an additional ticking clock element to the third act. In the film, Kirk orders Scotty to prepare the Enterprise‘s self-destruct sequence and that’s all we hear of it. The book actually has Scotty begin the countdown sequence and then explicitly wait for Kirk’s direct command to abort. This bit of additional danger is more direct than the abstract threat that V’ger poses to the Earth. Sure, wiping out all of humankind would be terrible, but blowing up the Enterprise is serious business.

You’re taking too long to get to the weird.

Okay, you know how I mentioned that there are two introductions? As noted, the first is by Admiral James T. Kirk. The second is by Gene Roddenberry, but not the Gene Roddenberry who actually wrote the book. It’s Gene Roddenberry as 23rd century narrative journalist, who interviewed the crew of the ship for this novel-length look at the V’ger incident.

This is a conceit that could have worked under steadier hands, but it quickly vanishes except for a scattering of footnotes here and there.

Anyway, you remember the striking opening sequence of the film, with the Klingon ships getting de-rezzed by V’ger? How would a better writer acting as a journalist have handled it? Maybe through a declassified Starfleet report of some kind? Perhaps they could provide the reader a garbled view of events using intercepted Klingon communications.

Roddenberry instead went with “Nah, Kirk’s got a skull implant and Starfleet’s surveillance network livestreamed the whole thing directly into his brain.” There’s a bit of handwaving about how top secret it all is, along with a footnote about the upcoming Mind Control Riots of the 2040s, but the idea of Kirk voluntarily sitting down for any kind of brain implant after the events of the original series just sits wrong with me.

In addition to HD Brain TV, Roddenberry brings up the idea of “New Humans,” telepathically-linked individuals who are devoting themselves to the exploration of inner space. This book never engages with them directly, thankfully, because I can’t imagine Roddenberry not making it deeply unpleasant.3Memory Beta’s entry on New Humans says they show up again in The Prometheus Design, a book I’ve never finished and am not looking forward to.

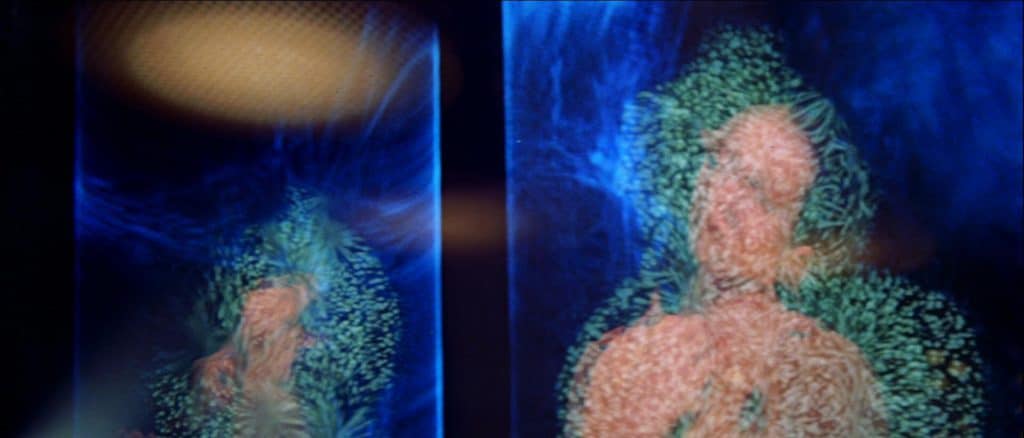

And speaking of deeply unpleasant, it’s time to talk about Vice Admiral Lori Ciani. We only see her very briefly in the movie. She’s the nameless woman melting on the transporter pad in a sequence that has been informing my nightmares for the last 35 years.

The novelization presents Ciani as Kirk’s partner, a xenopsychologist (spelled zenopsychologist by Roddenberry but c’mon) who helps the admiralty craft policy and maintain the peace in a diverse Starfleet. That sounds neat, right? Kirk seems to think so, too. After all, the two work together, share a home in San Francisco, and are in a marriage contract (one of Roddenberry’s more out-there ideas I think is actually kind of decent.)

However, it’s revealed early on that Ciani’s also the “tool” that Nogura has used to keep Kirk deskbound, and when Kirk finds out, Roddenberry’s misogynist streak comes to bear. It’s an ugly bit of narrative work for multiple reasons and it’s proven pointless when Kirk shrugs off her death and she’s never mentioned again.

I just plain hate the whole Lori Ciani thing because there’s so much that could be done with a character like that, even if she gets killed early on. Instead, her primary purpose seems to be to make sure the reader knows that Jim Kirk can still get a boner when she Facetimes him.

Okay, now we’re talking. Let’s get into the horny stuff.

Kirk’s stiffy is just the beginning. There is so much horny stuff to talk about here. Unfortunately, it also gets pretty squicky.

I’m just going to skirt around the fact that Roddenberry is functionally incapable of introducing a female character without asserting their attractiveness. That’s an ongoing motif in the man’s output. If you saw Star Trek on TV, it was obvious that the man liked leggy young dames wearing diaphanous outfits crafted by William Ware Theiss. 4To be fair, so do I, but there’s a thing called discretion, you know?

These are known quantities, and that’s fine, if not, you know, actually fine. In fact, I’ll be generous and say that there’s probably no better physical description of Nichelle Nichols’ Uhura than saying that she has “classically beautiful features.” I’m going to give him that wide a berth.

But not even grading on a curve can make me ignore what he does with Lt. Ilia, who was played by the former Miss India, Persis Khambatta.

Part of an alien race who are so mind-blowingly good at sex and excreting pheromones that they have to take an oath of celibacy to serve on Starfleet vessels, the Deltan navigator is some kind of 12th dimensional version of problematic. Early on in the novelization, it’s established that a younger Decker left her because he knew that if he was with her just once, he’d only want to be with her for the rest of his greatly-shortened life.

As you know, she gets zapped by V’ger, scanned, cloned, and that body is sent back as a way for the alien to communicate with the “carbon-based infestation” on board the Enterprise.

In short order:

- Kirk spends half a page ogling the naked Ilia-probe before grabbing the too-short terrycloth robe she spends the rest of the movie in.

- McCoy scans the probe and notes that every aspect of Ilia’s physiology is duplicated, even the ridiculously overactive exocrine system.

- Kirk realizes that the only person who can possible handle the pheromone soup that she’s sloshing everywhere is the man who was able to walk away from her, Decker. He tells the younger officer to find out what V’ger wants.

- In an effort to reach the part of Ilia that he senses is still there, Decker takes the probe to the recreation deck (where we learn there are sex rooms because of course there are) and has a brief breakthrough.

- Kirk asks if physical intimacy might be the key to talking to Ilia and learning more, because of course Kirk does. Decker tells him that it’s not Ilia, that the probe won’t have the memories of their relationship that might give him an in. He even compares the act to having sex with a photon torpedo.

- Still, something was there so Decker then takes the probe to Ilia’s quarters, where we learn that nice headband that Chapel presents her with is a loveband, a ceremonial gift from a Deltan man to a woman that is so laden with meaning that it basically acts as a Get Into Her Pants card. 5Turns out that back in the day, a culturally-innocent Decker bought it for her because he thought it was pretty and would look nice on her perfect skull.

In the final film, Ilia’s personality comes through again for a brief moment before V’ger re-assets control. It’s actually a pretty affecting scene and a testament to Khambatta’s acting abilities that she sells it so thoroughly.

Now, take a minute and see if you can suss out what happens when he puts it on her head in Rodddenberry’s novelization?

That’s right!

Decker has sex with the biomechanical creation in which his ex-girlfriend’s soul has been trapped. It doesn’t matter, though, because just like the movie, V’ger takes over, but this time it’s mid-coitus.

Gene Roddenberry, you really are the Gene Roddenberriest.

So you’ve got the good, the weird, and the horny. What else?

I mentioned earlier that Roddenberry abandoned his own “narrative journalism” framework and that the pacing was lumpy, but what’s immediately apparent to the reader is how bad the prose itself is. A lot of the time, it reads like a forgettable YA novel. Exclamation points are used with abandon, italics are abused for emphasis, and some sentences are just tortuously constructed.

(Yes, I see the irony of me pointing all this out.)

Here’s an example that stood out to me, the opening paragraph of Chapter 18:

The wispy edges of the cloud had looked like giant aurora borealis effects, the Enterprise whipping past and through towering graceful draperies of transparent colored light.

It’s awkward and overstuffed, filled with adjectives and adverbs, and says nothing on its own. It imparts none of the scale or grace that the sequence it’s describing has on screen. (I also hate its use of the quasi-passive past progressive verb form, which is not a crime but should be.)

However, it’s not all bad; there are some genuinely good passages that appear in the book, but it’s usually an accident of context versus deliberate skill. The gruesome horror of the aforementioned transporter accident sequence is served well by Roddenberry’s proclivities:

Shapes were materializing on the platform again – but frighteningly misshapen, writhing masses of chaotic flesh with skeletal shapes and pumping organs on the outside of the “bodies.” A twisted, claw-like hand tore at the air, a scream came from a bleeding mouth…

But short bits like this are the exceptions that prove the rule.

Oh, hey, speaking of “awkward and overstuffed,” please say there’s a conclusion coming. Please.

Okay, yeah, I’ve kept you here long enough. Here’s the takeaway.

Gene Roddenberry’s novelization of Star Trek: The Motion Picture is a bizarre artifact that’s fascinating on its own to a certain sort of fan. I happen to be just that. You can see some groundwork for tropes that would be recycled into the first season of Star Trek: The Next Generation. Really, though, it’s not worth the time for anyone who’s not interested in poking around the weird edges of the Star Trek mythos.